The exuberant optimism that had prevailed in Finland during the long economic boom and social liberalisation came to an end in late 1990 with a deep recession and harsh self-examination of the fundamental nature of architecture. At the same time, rapid developments in telecommunication technology and the emergence of the so-called Nokialand of Finland, fuelled interest in expressing the progressive Nordic welfare society through cool, minimalist aesthetics. This article examines the change in direction in 1990s architecture and presents some theoretical impulses behind the new features that emerged in Finnish architecture in the 1990s.

The Kaustinen Folk Arts Center (Rainer Mahlamäki / Kairamo–Lahdelma–Mahlamäki, winning entry to an open architectural competition held in 1990, compl. 1997) Photograph: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

The fuzzy face of architecture

At the dawn of the 1990s, Finnish architecture was in a state of division. The modern movement had long been in need of a radical push forward, but the direction of the new impulse was unclear. Postmodernism, which had arrived from abroad, had been viewed with suspicion throughout the previous decade, especially in its commercial form and in its most striking manifestations of classic revival. However, many postmodern ideas that crept into the discussion, such as cherishing the historical layers of architecture, appreciating the multisensory experience of architecture, and shaking up the formalism of stereotypical box architecture, were welcomed.

The postmodern critique was responded to by acknowledging the change in cultural values and the ideological stagnation of architecture. However, the solution was not to be found in the postmodernist style, but rather in resetting modern architecture to its origins and, as it were, re-examining the meaning of modern architecture by studying, for example, the architecture of Alvar Aalto [1]. The main programmatic thrust of the renewal of modernism was that, instead of the “overheated social drama of postmodernism” [2], the original idea of modernism and its unexplored side paths should be clarified. [3]

Poleeni Cultural Center in Pieksämäki (Gullichsen–Kairamo–Vormala Architects, open architectural competition 1982–83, compl. 1989) is a striking example of how the functionalism of the pre-World War II era could also be considered traditional Finnish architecture. Postmodern influences are evident in references to Mediterranean cultural history, Aalto quotations, and other atmospheric elements. Photograph: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

Rauma Government Building (Olli-Pekka Jokela and Pentti Kareoja, open architectural competition 1985–86, compl. 1992). The neo-functionalist architecture appears strikingly authentic. Inside, the popular 1990s trend of incorporating urban details such as park benches, street signs, and cobblestones into passageways called’ inner streets’ has been applied. Photograph: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

From dispersion to silence and the forgotten core of modernism

Juhani Pallasmaa’s essay “The Limits of Architecture – Towards an Architecture of Silence” (1990) interpreted the atmosphere of disunity and lifelessness that prevailed in architecture at the turn of the decade as a kind of Fukuyama-esque end of the Great Utopia in the grand narrative of architecture. Other Modernism would be a place- and situation-aware attitude that, instead of seeking attention, would appeal through its restrained and considered form, authentic materials, and situation- and culture-bound attitude. The key was to restore the autonomy of architecture: the shackles of techno-economic systems and the need to please an imaginary ‘general public’ had to be broken. [4]

The ideal of a deliberately restrained design language is supported by foreign architecture critics. Among others, the March 1990 issue of The Architectural Review, themed Cool Helsinki School, expressed its unreserved admiration for Finnish architects, who had stubbornly resisted the invasion of postmodernism and managed to renew themselves by combining the traditional modernist rationalism with postmodern sensuality. [5]

The idea of restoring the autonomy of architecture echoes the American and Italian avant-garde and deconstructivism of the 1970s, which were part of postmodern architectural thinking. The 1988 exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture [6], and the seminars and publications that followed, encouraged an interpretation of architecture in the spirit of philosopher Jacques Derrida and philosopher Gilles Deleuze as a unique language and to question the tenets of modernism regarding service to society, purity of form, and the relationship between space and function. In deconstructivism, basic architectural concepts such as wall, floor, roof, space, and place were redefined. “By penetrating the inner world of architectural language, revealing its formal structure, connections, and reflections, and then proceeding through layers of signs to the origin, we may reach the ur-phenomenon, the essential form,” wrote architect Ilmo Valjakka. [7]

Electrifying collage architecture

The combination of breaking down the modernist basic box, postmodern individualism, and the experiential nature of architecture produced an aesthetic reminiscent of 1920s Russian constructivism or the collision of Platonic forms – or alternatively, architectural expression could be reduced to the disciplined functionalism of the 1930s or allowed to break free into the boundless, fantastical, and strange, even violent, random coordinates made possible by new computer-aided design. [8] The paradigm of architecture in the new electronic age [9] questioned the traditional ethos of architecture as a single truth – a single main idea, a single main view, a single value system, a single ultimate meaning. A wall could both conceal and reveal, bend into a roof, novelty turn into pastiche, surface detach from mass, a sense of security turn into horror, the interior push outwards, light reveal otherness.

The exhibitions and lectures organized by the Museum of Finnish Architecture – for example, the exhibitions of Daniel Libeskind (1980), Zaha Hadid (1988), and Frank Gehry (1989) [10] – as well as the Alvar Aalto symposiums, provided significant ideological impetus for the renewal of the 1990s in this regard. However, individual building plans in Finland were not theoretical, but mainly reflected international architectural styles and ideological trends. The clearest examples of the late-modernist architectural concept in this regard are the Heureka Science Center (Heikkinen & Komonen, open architectural competition 1988, completed in 1989), the Kolinportti transport station in Juuka (Juhani Katainen and Olavi Koponen, invited competition 1990, completed in 1992), the Siilinjärvi swimming pool and leisure center (Esa Laaksonen, open architectural competition 1985–86, completed in 1992), the Emergency Services Academy Finland and dormitory in Kuopio (Heikkinen & Komonen, open architectural competition 1985–86, completed in 1992) and the Raisio library and auditorium (Hannu Tikka / Artto–Palo–Rossi–Tikka, open architectural competition 1995–96, completed in 1999). At their most intense, the solid and glass parts seemed to push towards each other and, upon colliding, burst forth with spirals, diagonal lines, inclinations, and protruding spikes; at its quietest, the cleanly cast concrete wall curved only slightly; at its most moderate, the architecture was a geometric collage in which different functions were arranged into their own spatial units.

Siilinjärvi swimming pool and leisure center (Arkkitehtitoimisto Esa Laaksonen Oy, open architectural competition 1988, compl. 1992). The architecture is based on the interplay created by the encounter of pure basic forms. Photograph: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

Emergency Services Academy Finland and dormitory in Kuopio (Heikkinen & Komonen, open architectural competition 1985–86, compl. 1992). The determined steadfastness and clarity of the architecture convey the confidence, alertness, thoughtfulness, and determination required of rescuers. Photograph: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

The new image of Finnish architecture

Alongside the transition from modernism to postmodernism, architects in the 1990s were confused by the computerisation of design and Finland’s rapid transformation from a cautious nation under the Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 to a telecommunications superpower intoxicated by the liberalisation of the market. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, EU membership in 1995, and the rapid growth of the IT sector led to overloaded CAD workstations processing technology villages and business parks. The door to Europe had already been opened in 1985, when an EU directive on the mutual recognition of architectural qualifications allowed European architects to work in any country in the European Economic Area; this opened up new training and employment opportunities for Finns as well. Finland’s first architectural policy program, introduced in 1998, aimed to enhance the international competitiveness of Finnish architecture by, among other measures, fostering international communication and establishing a register of qualified architectural designers.

The new, increasingly invigorating cross-border competition added pressure to update the public image of Finnish architecture. International comparability was emphasized, among other things, by publishing new books on Finnish architecture and inviting international architects to participate more closely in the development of the built environment. For example, the architectural competition for the Helsinki Museum of Contemporary Art in the autumn of 1992 was open to architects from the Nordic and Baltic countries, but four internationally renowned architects were also invited to participate, none of them with any experience in museum design: Coop Himmelblau Wolf D. Prix and Helmut Swiczinsky from Austria, Alvaro Siza from Portugal, Kazuo Shinohara from Japan, and Steven Holl from the United States. A total of 516 competition entries were submitted, of which Steven Holl’s Chiasma proposal from the United States was selected for implementation in 1993.

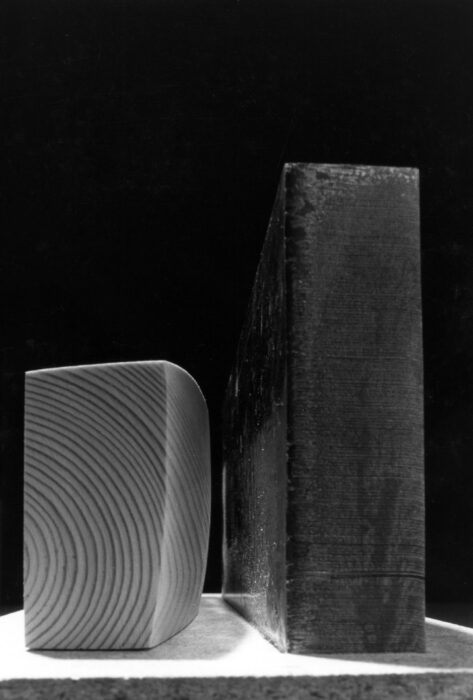

A more symbolic example of the international nature of Finnish architecture is the Helvetinkolu [Hell’s Corge] pavilion at the 1992 World Expo in Seville (open architectural competition in 1989). The clattering collision between the wooden ‘Keel’ and the steel-framed ‘Machine’ made a jaw-dropping impact, instantly revealing the open-mindedness of a young generation of architects who were exploring the essence of Finnish culture on the axis between the modern and the traditional and making their interpretations into unapologetically sculptural and descriptive architecture.

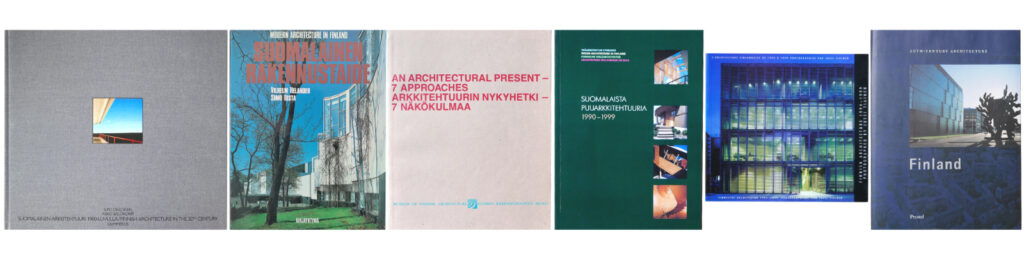

Books about Finnish architecture, especially those aimed at an international audience, from the end of the last century. From left to right: Suomalainen arkkitehtuuri 1900-luvulla – Finnish Architecture in the 20th Century (1985), Suomalainen rakennustaide – Modern Architecture in Finland (1987), An Architectural Present: 7 Approaches – Arkkitehtuurin nykyhetki: 7 näkökulmaa (1990), New Finnish Architecture (1996), Suomalaista puuarkkitehtuuria 1990–1999 (1998), Finnish Architecture 1994–1999 (1999), and 20th-century Architecture: Finland (2000). Collage: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

Books about Finnish architecture, especially those aimed at an international audience, from the end of the last century. From left to right: Suomalainen arkkitehtuuri 1900-luvulla – Finnish Architecture in the 20th Century (1985), Suomalainen rakennustaide – Modern Architecture in Finland (1987), An Architectural Present: 7 Approaches – Arkkitehtuurin nykyhetki: 7 näkökulmaa (1990), New Finnish Architecture (1996), Suomalaista puuarkkitehtuuria 1990–1999 (1998), Finnish Architecture 1994–1999 (1999), and 20th-century Architecture: Finland (2000). Collage: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

Helvetinkolu [Hell’s Corge], Expo’92, Sevilla, Espanja (Juha Jääskeläinen, Juha Kaakko, Petri Rouhiainen, Matti Sanaksenaho, and Jari Tirkkonen (1989–92). Photograph of the competition model. © Architecture & Design Museum

Space trusses, double-glazed facades – and wood

The re-evaluation of Finland’s international image is particularly evident in the office buildings and airports constructed in the 1990s. Rovaniemi Airport (Heikkinen & Komonen, 1992) rejected Lapland exoticism and offered the growing number of tourists a steel box and two art installations that visualised the Arctic Circle and the Earth’s annual journey around the sun. The two-stage expansion of Helsinki-Vantaa Airport’s T2 terminal (Pekka Salminen, 1996–99) turned air travel into a comprehensive leisure experience: airy glass and steel structures flooded the triangular interior spaces with light.

Nokia’s headquarters in Espoo (Helin & Siitonen Architects, invited competition 1983, completed 1997) became a symbol of Finland’s rise as a model country in the information age. The extensive use of glass was intended to promote interactivity, openness, and encounters. The most confident example of steel and glass architecture was presented in the Sanomatalo building (Sarc Architects, invited competition 1995, completed 1999), whose skilful double-glazed facades showed the pulse of the media newsroom to the people of Helsinki 24 hours a day, but which critics criticised for being disconnected from the surrounding urban structure.

However, the 1992 World Expo pavilion Helvetinkolu had already demonstrated that the design language most characteristic of forest-rich Finland was, after all, expressed through wood. The national wood construction program was launched for the first time in 1994. In the same year, the international master’s program in wood architecture, known as the Wood Program, began at the then Helsinki University of Technology. The Forest Information Centre Lusto in Punkaharju (Ilmari Lahdelma, Rainer Mahlamäki, and Juha Mäki-Jyllilä, open architectural competition 1990–91, completed in 1994) had to rely on concrete as the frame material, but left the building materials honestly exposed.

The Kaustinen Folk Arts Centre (Rainer Mahlamäki and Ilmari Lahdelma, open architectural competition 1990, completed 1997) combined wood with granite: the large cultural centre was planted in a Central Ostrobothnian rural town by embedding part of the premises into a rocky slope and dividing the rest of the space into wooden-surfaced sections. The combination of bare rock, concrete, wood, ramps, and spatial sequences was festive and nationalistic without being mystifyingly folksy. Another apt example of the relationship between postmodern architecture and local building traditions and the formal language of folk architecture is the small cultural centre Juminkeko in Kuhmo (Heikkinen & Komonen, 1999), which recycled the former district office of the Finnish Forest Administration, built in the 1950s, into a minimalist wooden structure supported by log pillars and covered with a turf roof. The ideals of our architecture in the 1990s – uniqueness, functionality, clarity, and authenticity – and the traditional virtues of Finnish building culture finally found each other at the dawn of the new millennium.

Info Centre Korona, Helsinki (ARK-House Architects, invited architectural competition 1996, compl. 1999). The new science library in the developing campus area of the University of Helsinki in Viikki reflects the functional change in traditional university libraries. The blue cylinder also features administrative and learning spaces, as well as winter gardens that serve as meeting and reading areas, and it forms a notable landmark. The amount of sunlight flooding through the double-glazed facade is regulated by wooden slats and louvres, which became a fashionable design feature in the 1990s. Photograph: Harri Viljamaa CC BY-SA 4.0

Heikkinen & Komonen. Cultural centre Juminkeko, Kuhmo, 1999. The cultural centre, which focuses on the Kalevala and Karelian culture, is familiar and vernacular without being romantically nationalistic. Photograph: Anni Vartola CC BY-SA 4.0

Anni Vartola

___________________________________

Footnotes

[1] Norri, 1979; Mikkola, 1981; Mäkinen et al., 1985.

[2] Pietilä, 1983, 75.

[3] Pietilä, 1984.

[4] Pallasmaa, 1990.

[5] Davey et al., 1990, 28-29.

[6] Johnson and Wigley, 1988.

[7] Valjakka, 1988.

[8] Valjakka, 1988; Verwijnen, 1988; Bonsdorff, 1989; Ahlava, 1999.

[9] Eisenman, 1996.

[10] Pietilä, 1982; Pallasmaa, 1986; Friman, 1990.

References

Ahlava, Antti. Kauhun arkkitehtuurin jälkeen [Beyond architecture of horror]. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 5/1999, p.18-25.

Bonsdorff, Pauline von. Poissaolon metafysiikka: Dekonstruktiosta. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 3/1989, p.34-37.

Davey, Peter, Colin St John Wilson, Richard Weston, Marja-Riitta Norri & J. M. Richards. Cool Helsinki School. The Architectural Review, 3 March 1990, p.27-77.

Eisenman, Peter. Visions’ unfolding: Architecture in the age of electronic media (1992). In: Theorizing a New Agenda for Architecture – An Anthology of Architectural Theory 1965-1995, toim. Kate Nesbitt. New York: Princeton Architectural Press 1996, p.556-561.

Friman, Kimmo. Karppi kuivalla maalla. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 1/1990, p.20-21.

Gullichsen, Kristian. Pieksämäen kulttuurikeskus. Suunnitelma. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 8/1985, p.66-67.

Gullichsen, Kristian. Kulttuurikeskus Poleeni, Pieksämäki. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 8/1989, p.44-46.

Heikkinen, Mikko ja Markku Komonen. Rovaniemen lentoasema. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 6/1990, p.40-42.

Heikkinen, Mikko ja Markku Komonen. Valtion pelastuskoulu ja asuntola, Kuopio. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 1/1993, p.24-32.

Heikkinen, Mikko ja Markku Komonen. Juminkeko, Kuhmo. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 6/1999, p.34-37.

Huttunen, Hannu, Markku Erholz ja Pentti Kareoja. Infokeskus Korona, Helsinki. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 6/1999, p.26-31.

Johnson, Philip & Mark Wigley. 1988. Deconstructivist Architecture. Ed. James Leggio. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Jääskeläinen, Juha; Juha Kaakko, Petri Rouhiainen, Matti Sanaksenaho, Jari Tirkkonen. Helvetinkoulu / Suomen paviljonki Sevillan maailmannäyttelyssä. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 4–5/1992, p.40-46.

Laaksonen,Esa. Siilinjärven uimala ja vapaa-aikakeskus, Siilinjärvi. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 1/1993, p.16-21.

Mahlamäki, Rainer. Kansantaiteenkeskus, Kaustinen. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 2/1998, p.24-29.

Mukala, Jorma. Ideologiapeli: Arkkitehtuurin tilannekatsaus [The ideology game: An architectural review]. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 6/1999, p.18-25.

Mikkola, Kirmo, ed. 1981. Alvar Aalto vs. the Modern Movement / Alvar Aalto ja modernismin tila. Helsinki: Rakennuskirja Oy.

Norri, Marja-Riitta. Alvar Aalto -symposium. Jyväskylä 1.–3.7.1979. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 5–6/1979, p.24-30.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. Frank O. Gehry – myöhäismoderni anarkisti [Frank O. Gehry – A late-modern anarchist]. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 5/1986, p.24-35.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. Rakennustaiteen rajat – kohti hiljaisuuden arkkitehtuuria [The limits of architecture – Towards an architecture of silence]. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 6/1990, p.26-39.

Pietilä, Reima. Kahdeksan tapaa päästä laatikkoarkkitehtuurista. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 2/1979, p.39-41,50.

Pietilä, Reima. John Hejduk ja modernin arkkitehtuurin autenttisuuden mittaluvut. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 4–5/1982, p.30-31.

Pietilä, Reima. Kaamoslukemista. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 1/1983, p.74-77.

Pietilä, Reima ja Raili. Päiväkoti Taikurinhattu. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 8/1984, p.22-31.

Salminen, Pekka. Helsinki-Vantaan lentoasema, keskiterminaalin 1. vaihe. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 3/1996, p.26-35.

Salminen, Pekka. Avaruusristikon alta yläilmoihin. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 1/2000, p.40-45.

Salokorpi, Asko, ed. 1985. Classical tradition and the Modern Movement. The 2nd International Alvar Aalto Symposium, 6–8 August 1982. Helsinki: Finnish Association of Architects, Museum of Finnish Architecture, Alvar Aalto Museum.

Siikala, Antti-Matti. Lehtitalon syke kohtaa kaupungi”. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 1/2000, p.64-69.

Valjakka, Ilmo. Todellisuuden ikuinen tulkinta. Dekonstruktio – arkkitehtuuri. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 6/1988, p.81-82.

Verwijnen, Jan. Rem Koolhaas and Office for Metropolitan Architecture OMA. Arkkitehti – The Finnish Architectural Review 5/1988, p.30-43.